What Is Shmita: The Sabbatical Year?

Every seven years, Jews in Israel, observe the biblical laws of shmita, the “year of release,” which is more widely known as the sabbatical year. This year, the Jewish year of 5782, shmita began on Sept. 7, 2021. While the observance of this biblical law is only applicable in the land of Israel today, its spirit is something that can, and should, permeate everywhere.

The basic laws of shmita, which are outlined in several places in the Bible, demand that we cease from cultivating the land, that we release all debt, and that we relinquish ownership of anything that grows in our fields. According to the biblical law, all produce in the country of Israel becomes “ownerless” as soon as the shmita year begins, rendering it free for the taking by anyone.

At the end of every seven years thou shalt make a release. — Deuteronomy 15:1, KJV

The Key to Understanding Shmita

The key to understanding the spirit of shmita is to understand the weekly Sabbath. In fact, the year of shmita is also referred to as “a Sabbath to the LORD” (Leviticus 25:4). Just as we work for six days and rest on the seventh, we work the land for six years and rest on the seventh.

The purpose of the Sabbath is to remember that God is the true Creator. So, too, the year of shmita reminds us that God is the Creator and Owner of all. The weekly Sabbath ensures that we have time to focus on God, our families, and our faith, and the year of shmita gives us time to focus on all three of those fundamental values — especially on faith.

Faith is the primary value of the shmita year. The Bible addresses the obvious question: If we don’t work the land, then what will we eat? God promises that those who trust Him and observe the laws of shmita will benefit from extreme abundance – so much so that what grows in the sixth year will be enough not just for the seventh year, but until the ninth year when the new crops come in. Those who rely on faith in this year of shmita will be richly rewarded.

The Social Aspect

From a social perspective, shmita is the great equalizer. The laws strive to achieve two separate goals simultaneously: to lift up the poor, and to humble those who are wealthier.

In Exodus 23:11 we read, “ . . . during the seventh year let the land lie unplowed and unused. Then the poor among your people may get food from it.”

Notice that there are two directives in this verse. The first is that the land cannot be worked. This relieves the landowner from feelings of ownership and releases him from the pitfall mentioned in Deuteronomy 8:17: “You may say to yourself, ‘My power and the strength of my hands have produced this wealth for me.’”

In the year of shmita, anything that grows is God’s doing, not ours. It reminds the landowner that the land and everything in it belongs to God. While we may be entrusted with God’s abundance, ultimately, everything belongs to Him and it is our duty to share what we are given.

Care for the Poor

The second part of the verse is more straightforward. It simply states that the poor are permitted to eat whatever grows in the land of Israel for the entire year. This is more than just a handout to the hungry. Because the landowner hasn’t done anything to produce the food of the land, the poor person may collect with dignity knowing that he is being fed not by the hand of man, but straight from the hand of God.

In addition, another rule of shmita is that all debts in Israel must be cancelled: “At the end of every seven years you must cancel debts . . . They shall not require payment from anyone among their own people, because the LORD’s time for canceling debts has been proclaimed” (Deuteronomy 15:12).

Once again, the poor are uplifted as they get a “second chance” financially. The creditor, on the other hand, learns that it was never his money to begin with. He was simply doing the bidding of the Lord, and now God sees fit to give the poor man another chance.

The Spiritual Aspect

We live in a world that functions according to cycles. The daily cycle is dictated by periods of light and darkness, the monthly cycle regulated by the waxing and waning of the moon, and the yearly cycle follows the orbit of the sun.

However, the world also follows the weekly cycle which has no basis in nature whatsoever. The only reason for the seven-day cycle is because God created the world in six days and rested on the seventh.

The cycle of seven, which also dictates our shmita cycle, is intrinsically spiritual. It is a pattern that was created by God and affirms His mastery over all creation. Simply by observing this pattern, whether it be weekly or on a septennial basis, we affirm that we live our lives according to a spiritual paradigm, not just according to physical patterns.

The seventh year has much in common with the seventh day of every week. In fact, in multiple places in the Bible the word “Sabbath” is used in connection to the year of shmita, just as it is to our weekly rest.

The “Sabbath to the LORD”

The shmita year is “a sabbath to the LORD,” a time when we are free from the yoke of physical labor and mundane living so that we are able to concentrate our time and energy on spiritual endeavors – both individually and collectively.

Another paramount aspect of the shmita year is strengthening our faith in God. As the Bible addresses, there is a great concern for what the people will eat if they don’t work the land. The solution is faith in God – that He is the ultimate provider whether we work the land or not

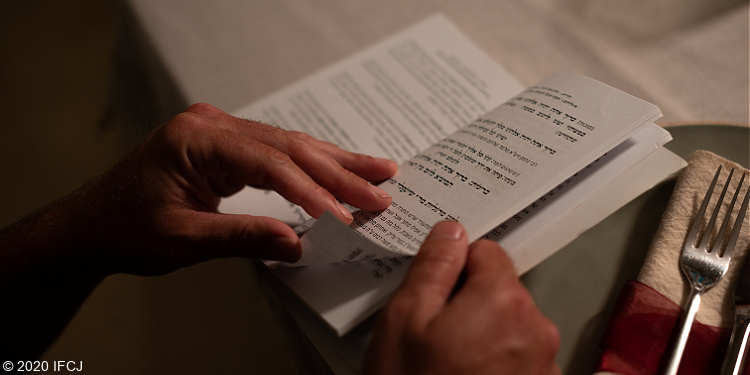

The courage to observe the laws of shmita requires an immense amount of faith, so exercising our faith is a central component during the year of shmita. Additionally, this most sacred year is a time for studying God’s Word, contributing to God’s purposes, and re-evaluating the spiritual direction of our lives.

The Agricultural Aspect

When God first created man, there was a state of harmony between God, man, and the earth. Adam was placed in Eden and charged with the duty “to work it and take care of it” (Genesis 2:15). However, when Adam and Eve ate the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge – which had been prohibited by God – that harmony and unity were shattered. No longer would humanity enjoy the perfect balance, peace, and tranquility that briefly enveloped the world.

The laws of shmita were intended in part to restore that lost equilibrium. As we refocus our relationship with our Creator, we also revisit our relationship with the earth. We take a break from working the land and focus on caring for the land.

According to Maimonides — a medieval rabbi and scholar — the purpose of shmita is to make the earth more fertile and stronger by letting it lie fallow. We become keenly aware that the earth is not ours to use and abuse; rather it is God’s creation that we are to steward. To ignore the needs of the land is to sever the bond that should unite man, Adam, with the earth, Adama.

By letting the land rest, we honor God and express our gratitude for all that He provides. By the end of the shmita year, we can potentially restore the harmonious relationship that existed at the beginning of time, and that is destined to be reinstated once more.

Test your knowledge on Shmita with our quiz, “Shmita: The Sabbatical Year.”.

The Observance of Shmita in Israel Today

Today, the land of Israel is in transition. We have experienced the fulfillment of many biblical prophecies, but Israel is yet to become the fully Torah-centered country that God intended. Likewise, the observance of shmita is also in a transitional phase. On one hand,there is more awareness and observance of these laws than there has been in the past 2,000 years. On the other hand, due to many factors, including modern-day living and the diverse demographics within the state of Israel, we still have a long way to go until shmita is observed fully as described in the Torah.

For those who observe the laws, there are several main prohibitions: We are not allowed to plant anything new or prune any plants or trees in order to stimulate growth. Harvesting and gathering produce for the sake of selling and making a profit is also prohibited. Other activities that stimulate growth, such as fertilization, weeding, and spraying pesticides are also not allowed, except in extreme cases.

So what do shmita-observant Israelis eat during the year?

There are several options. The first is to eat produce that grows naturally during the shmita year and that is gathered according to specific laws governing how produce may be acquired. This produce is considered holy and must be treated accordingly. Many homes have a special bin designated for the remnants of this holy produce. Often, the words Kedushat Shivi’it, “Holiness of the Seventh,” is written on it. When the bin is full, the contents are disposed of in a dignified manner.

Practical Steps to Capture the Spirit of Shmita

- Give yourself a break. Take some time off to rest and re-evaluate your life.

- Donate time. Set aside an extra hour a week for acts of kindness and community service

- Contribute financially. This is the year for giving more than other years. Pick a favorite cause or charity and support it. As you give, give with faith.

- Study God’s Word. Set aside a time every week to study the Bible and meditate on God’s Word

- Pray powerfully. As a year of faith, prayer is particularly relevant this year. Pray harder, deeper, and with more faith

- Explore God’s creation. This is a year that honors nature. By spending time outdoors we cultivate our gratitude for the land and connect with God, the Creator of all land.

- Be a good steward. Be aware of the effects of waste and pollution and do your part to keep our God-given world healthy and clean.