My Grandfather’s Story: Part Three

Yonit Rothchild | April 8, 2017

In the month leading up to Yom HaShoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, which falls on April 8th this year, Yonit Rothchild, a writer working with The Fellowship in Israel, will be sharing the moving story of her grandfather, a Holocaust survivor. This week, he makes a brave gamble for his freedom.

“My grandfather, Max Grinblatt of blessed memory, had two requests in life. One was to watch over our children; the other was to tell the story of the Holocaust so that the world would never forget. This is his story.” – Yonit Rothchild

Part III: The Great Escape

My grandfather had many names. Shortly after his birth, he was named in the synagogue Mordechai Gimpel ben (son of) Moshe. That name accompanied him throughout life, first by his Jewish family and friends in Poland, and then anytime he participated in a Jewish ritual or life-cycle event for the rest of his life.

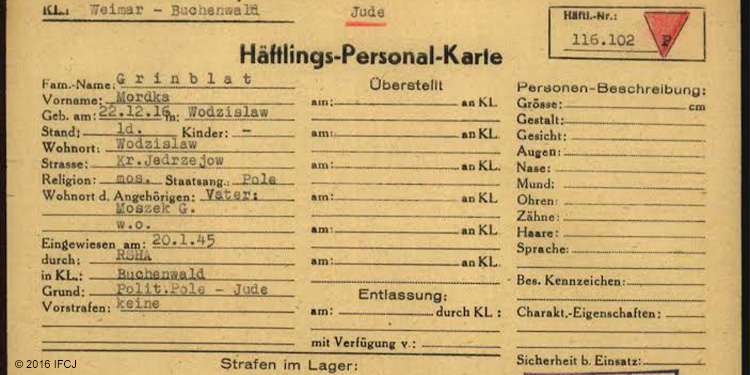

My grandfather also received a non-Jewish name when he was born. He was officially Mordka, a secular version of his Jewish name, which appears on all his official documents until his immigration to America. After the Holocaust, when my grandfather moved to the United States, he became Max, a solid American name that he proudly went by for most of his life.

Still, there was one more name that my grandfather assumed during his lifetime which was probably the most important name of all. My grandfather became Genik Czakovsky for a short time in 1945 – and it was this name that saved his life.

A Glimmer of Hope

My grandfather’s escape from the Nazis began with a glimmer of hope. In the winter of 1945, my grandfather was wasting away in the Buchenwald concentration camp when he heard the sound of warplanes flying overhead. At first he thought that the camp was about to be bombed. But what those American pilots dropped from their planes was not bombs, but papers.

They dispersed thousands of leaflets all over the concentration camp with the words, “Don’t give up. The war is coming to an end. It won’t be long!” My grandfather’s joy, as well as that of the other inmates, was immeasurable. They had survived years of hell, and now they were just months away from freedom.

However, the Nazis also knew that the war was coming to an end. They were well aware that they would not emerge victorious. So they began the process of destroying the evidence of their unspeakable crimes. This meant getting rid of the remaining prisoners. They didn’t want anyone left alive who could tell what they did.

A Gusty Gamble

My grandfather was woken in the middle of the night and placed together with those still alive in Buchenwald onto an open cattle car. It was snowing as the train pulled away, and the open cart allowed the cold snow to fall on my grandfather’s shirtless body. As the transport moved on, some died from the sheer cold.

At one point, the train stopped along the border of Czechoslovakia. There were a number of non-Jewish Czech prisoners on the train. (Don’t forget that five million non-Jews were also killed in the Holocaust.) When the train halted, the Czech prisoners began to shout to their countrymen: “We are your brothers! We are Czech! We are starving, and they are killing us!”

One thing led to another, and the mayor of the town approached the Nazis demanding the release of all the Czech prisoners. The Nazis agreed – for a hefty ransom per prisoner – but were ruthless in who they considered eligible for release. The first order was to determine who was Czechoslovakian. They called for all Czechoslovakian men to come forward. Sensing that this was his only chance at survival, my grandfather looked at his brother and said, “We have blond hair and blue eyes. We are not Jewish; we are Czech.” My grandfather’s brother understood; they were about to gamble with their lives.

A New Name

The next step was to determine who could go and who had to stay on the train of death. Each person who stepped forward as a Czech was asked why they had been taken by the Nazis. If the individual had a plausible story about being in the wrong place at the wrong time, he was granted freedom. If not, he had to stay on the train.

When it came to my grandfather’s brother, Beryl, he told the Nazi that his name was Joseph Czaikov and he made up a story which the Nazis believed. He had gambled and won, and was allowed to stand with the other men to be freed. My grandfather was next. He stated that he was Genik Czakovsky, but his story did not convince the Nazis. He was ordered to the line doomed to stay on the train. He had lost.

But what happened next is what I see as nothing short of a miracle. The next man to be questioned was a Gypsy, dark-skinned, and very obviously not Czech. One has to wonder why he even tried to pass off as one in the first place. When the Nazis took one look at him and ordered him to stay on the train, the Gypsy went crazy and created a scene. That distraction gave my grandfather the cover he needed to switch to the line of those determined to be Czech, and he did.

Long-Awaited Freedom

My grandfather could hardly believe it when he was placed in a truck with his brother and the other men let off the train on that cold, snowy day. The mayor announced, “You are now free!” The town provided the first set of clean clothing my grandfather had worn in six years and his first shirt in two-and-a half years. He received the proper food and shelter that had become a distant memory.

Slowly, my grandfather regained his health and humanity. He still had a long road to travel, but he was free. The nightmare was over. He had cheated death and won — with much help from above.