What Is Tisha B’Av?

The Fellowship | July 18, 2023

Tisha B’Av (the Fast of the Ninth of Av) is the darkest day on the Jewish calendar, a day of communal mourning to commemorate the many tragedies that have befallen the Jewish people, many of which have occurred on the ninth day of the Jewish month of Av. In particular, Tisha B’Av commemorates the destruction of the two Jerusalem Temples which occurred on the ninth of Av hundreds of years apart—the first in 586 BCE (Before the Common Era) and the second in 70 CE (Common Era).

Tisha B’Av, one of two “full-day” fasts in the Jewish year (the other occurs at Yom Kippur), is the culmination of a three-week period of mourning called “The Three Weeks” in English or Bein HaMitzarim (literally, “between narrow straits”) in Hebrew. This name comes from a verse in the Book of Lamentations, which is traditionally read on Tisha B’Av:

Judah has gone into captivity,

Under affliction and hard servitude;

She dwells among the nations,

She finds no rest;

All her persecutors overtake her in dire straits. (Lamentations 1:3, NKJV)

The three weeks of mourning begins with the fast of Shivah Asar B’Tammuz (meaning the 17th day of the Hebrew month, Tammuz), which was instituted to mark the breach of the Jerusalem walls during the Babylonian siege in 586 BCE. According to tradition, it also marks a number of other tragedies that befell the Jewish people after that day, including the halting of daily temple sacrifices and the burning of the Torah after the Babylonian invasion, and the erection of idols in the Temple during the Roman occupation. It is also considered the day on which Moses broke the first set of tablets containing the Ten Commandments after coming down Mt. Sinai to discover the people worshiping the golden calf. (See Exodus 32.)

A Time of Mourning Begins

The three weeks leading up to Tisha B’Av are viewed as a time of quasi-mourning, a time devoted to solemnity and reflection. During this time, the Jewish people refrain from personal indulgence and joyous activities. Weddings, parties, and other festive events are not permitted. In the last nine days of this period, leading up to the ninth of Av, the intensity of mourning increases—people refrain from eating meat or drinking wine; bathing, beyond what is absolutely necessary, is prohibited, as is doing laundry, and buying or wearing new clothes.This period of mourning concludes in the Fast of Tisha B’Av, a day that is spent entirely in mourning—fasting, praying, sitting on stools instead of chairs, and reading the Book of Lamentations, a poem recounting the prophet Jeremiah’s grief for the fallen city of Jerusalem. Fellowship Founder Rabbi Yechiel Eckstein wrote in his book, How Firm a Foundation, “[Tisha B’Av] is the blackest, most sorrowful day in the Jewish year. . . . Unlike the fast of Yom Kippur, which is one of repentance, that of Tisha B’Av is one of mourning and sadness” (p. 129).

“We are to vicariously feel the depth of grief and sadness that has marked this date throughout history,” Rabbi Eckstein wrote. “For we, too, are mourners on Tisha B’Av; we too, ‘let [our] tears flow like a river day and night” over the fall of Jerusalem” (Lamentations 2:18).

A Day of Tears

The tears we shed on Tisha B’Av are primarily associated with the destruction of the First Temple in 586 BCE and the Second Temple in 70 CE; however, the origins of this tragic day go back centuries earlier.

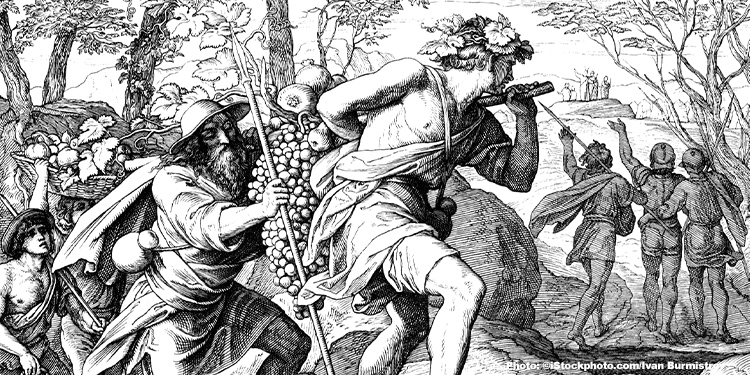

The year was 1313 BCE when the Israelites were on the threshold of entering the Promised Land. Two years earlier, they had been freed from Egypt through God’s powerful miracles, including the 10 plagues and the parting of the Red Sea. They had already experienced the revelation of God at Mt. Sinai and received His Word in the Torah. Indeed, they had been blessed with many of God’s loving miracles.

Before entering the land, Moses had sent out 12 spies to bring back a report about the land. When the spies returned, all but two of them gave a bad report about the land. They determined that the land was unconquerable. That night, the ninth of Av, “all the members of the community raised their voices and wept aloud” (Numbers 14:1). They cried because they wanted to return to Egypt. They cried about their circumstances. But ultimately, they cried for nothing because God had already shown them that with Him, they could do anything.

According to our Oral Tradition, that night God decreed, “Tonight they cried for nothing, so in the future I will give them a reason to cry!” Those words sealed the fate of generations to come. Both the First and Second Temples were destroyed on Tisha B’Av, marking the most agonizing and painful periods for the Jewish people, resulting in an exile whose ramifications are still felt today.

Throughout history, the Jewish people have suffered numerous tragedies that have occurred on the ninth of Av. In 133 CE, the few remaining Jews in Israel rebelled against the Romans. The rebellion was finally squelched on Tisha B’Av and hundreds of Jews were brutally butchered. Exactly one year later, the Temple Mount was razed so that a pagan temple could be erected. In 1290, again on Tisha B’Av, the Jews were expelled from England. In 1492, on Tisha B’Av, the Jews were kicked out of Spain. World War II and the Holocaust were the direct results of World War I which began, of course, on Tisha B’Av.

Tears that Count

The Jewish sages teach that after the destruction of the First Temple, the prophet Jeremiah accompanied the Israelites to the Euphrates River, at which point he informed them that he was returning to Israel to stay with the few remaining Jews there. The people began to weep inconsolably. Jeremiah said to them, “I testify in the name of God that if this sincere cry would have transpired moments ago, when we were still in our homeland, the exile would never have come about.”

Indeed, there is an appropriate time to weep. There is an opportune time to cry out to God. Tisha B’Av is one of those times. It’s a time to cry sincere tears of repentance and longing for God. It’s a time to regret past mistakes and to long for a better future with a restored relationship with God. These are the tears that God desires, and the tears that can open doors to salvation.

When the Israelites were enslaved in Egypt, it wasn’t until they cried out to God that the wheels of salvation began to turn. Similarly, our personal redemption, and that of the world, will come about when we turn to our Father in heaven and cry out to Him with sincere heartfelt prayer.

Tisha B’Av is a time to weep for what really matters in life. We weep for the shattered relationship between God and His children. We remember that all evil in this world is a direct result of the loss of God dwelling in our midst. As we read in the Book of Lamentations on Tisha B’Av, “pour out your heart like water in the presence of the LORD.”

A Day of Hope

Yet, even this saddest of days for the Jewish people, is not without hope. In the afternoon, the people rise from their mourning stools and recall the tradition that says in messianic times, this time of mourning will turn into a time of great joy and celebration. On the Sabbath following Tisha B’Av, and on the next seven Sabbaths leading up to Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish new year), prophetic selections of consolation are read.

A story is recorded in the Talmud that took place after the destruction of the Second Temple. When Rabbi Akiva and his colleagues came to Mt. Scopus and witnessed the Temple’s destruction, they tore their clothing in mourning. When they got to the Temple Mount itself and saw foxes running around where the Holy of Holies once stood, they cried. But Akiva laughed.

“Why are you laughing?” the rabbis asked. “Why are you crying?” Akiva replied. The rabbis explained that they were looking at the holiest place in the world and “now foxes run through it! How could we not cry!” Akiva replied, “That is why I am laughing.”

He continued, “One prophet said, ‘because of you, Zion will be plowed like a field’ (Micah 3:12). Another prophet said, ‘Once again men and women of ripe old age will sit in the streets of Jerusalem, each of them with cane in hand because of their age. The city streets will be filled with boys and girls playing there (Zechariah 8:4–5). Since the words of one prophet have been fulfilled, I now know that the words of the other prophet will also be fulfilled.” To this the rabbis exclaimed, “You have comforted us Akiva, you have comforted us.”

Never Forget Our Trials

As Rabbi Eckstein wrote, Tisha B’Av is a “reminder that despite the adversities and affliction marking Jewish history, God’s covenant with this people, Israel, remains in effect; his promise of redemption yet fulfilled, ‘The LORD your God will restore your fortunes and have compassion on you, and he will gather you again from all the peoples where the LORD your God has scattered you’” (Deuteronomy 30:3).

While some may think it strange to dwell and focus on such suffering and horrendous events, it is, in fact, biblical for Jews to not forget. The psalmist wrote in Psalm 137:5-6: “If I forget you, Jerusalem, may my right hand forget its skill. May my tongue cling to the roof of my mouth if I do not remember you, if I do not consider Jerusalem my highest joy.”

And so, as Rabbi Eckstein wrote, “We continue to commemorate past tragedies, not to wallow in our grief, but to strengthen our memory of history, in order to ensure that such things may never happen again. And, perhaps, our remembering will help us realize that our survival of these many trials is indeed a miracle, a gift from God.”