What Is Passover?

The Fellowship | April 16, 2024

Over the past 3,000 years, Passover (Pesach in Hebrew) has endured as one of the most celebrated and widely observed Jewish holidays. The Passover holiday, which begins this year at sundown on April 22 and ends at sundown on April 30, commemorates the seminal event in Jewish history—the story of the Exodus which led to the birth of the Jewish nation, Israel. In addition, the most basic and fundamental principles found in Judaism—faith, prayer, deliverance, freedom, and service to God—are woven into this timeless story.

It’s one of the foundational stories in the Hebrew Bible (which Christians know as the Old Testament): Moses leading God’s people out of Egypt, away from Pharaoh and out of slavery. The suffering of the children of Israel and their deliverance from slavery reaffirms our faith that God protects, provides for, and deeply loves His people and that He hears our prayers.

Learn more about the story of the Exodus with our Bible study: The Passover Experience

The command to observe Passover is found in Exodus 12 which reads:

The LORD said to Moses and Aaron in Egypt, “This month is to be for you the first month, the first month of your year. Tell the whole community of Israel that on the tenth day of this month each man is to take a lamb for his family, one for each household… That same night they are to eat the meat roasted over the fire, along with bitter herbs, and bread made without yeast… Eat it in haste; it is the LORD’s Passover.” (Exodus 12:1-3, 8, 11)

Once a year, Jews devote an entire week to recalling the events of the Exodus, internalizing these messages, and growing in their faith. One way they do this is through the ritual Passover meal known as the seder, which is the heart of the Passover celebration. At the seder meal, the Haggadah is read. This is the text that has been used for all of these generations to guide the seder, saying: “For God did not redeem our ancestors alone, but us, as well.”

The Story of Passover?

The story of the Exodus has its roots in the Book of Genesis. Four hundred years earlier, Jacob and his sons had settled in the land of Goshen because of a great famine in their homeland of Canaan. In Egypt, they prospered, thanks in large part to Joseph (Genesis 46:28–47:27). Due to a series of circumstances ordained by God, Joseph became the No. 2 man in all of Egypt, overseeing the preparations of the people to survive the famine, and thus, helping his own kinsmen survive, as well. Eventually, Joseph died, as did the Pharaoh whom he had served. That is when life began to change dramatically for the Israelites.

As events begin in Exodus 1, the population of the Israelites had grown to such proportions that they posed a perceived threat to the new Pharaoh (Exodus 1:9–10). To deal with this growing problem, Pharaoh enslaved the Israelites and forced them to build his great cities. When that proved ineffective, Pharaoh took more drastic measures, ordering the Hebrew midwives to kill all the male babies.

When the midwives refused to obey the Pharaoh, he issued another edict to his people: throw all the Hebrew male babies into the Nile River. Yet, God overturned the Egyptians’ final scheme in a most unusual way—through the birth and divine deliverance of a particular Hebrew boy, Moses (Exodus 2:1–10).

The story of Moses is a familiar one. The Pharaoh’s own daughter discovered Moses floating in a basket in the Nile River, and having compassion on the baby, adopted him as her own. Moses grew up with all the privileges of an Egyptian prince, yet apparently never forgot his Hebrew roots.

God Chooses Moses

When he was 40 years old, Moses was walking among the Hebrew workers, he witnessed an Egyptian abusing one of the Hebrew slaves. Moses intervened, killing the Egyptian and hiding his body in the sand. Moses thought his act would be appreciated by the Hebrews, but he was wrong. And when he learned that Pharaoh undoubtedly had heard about his crime, Moses fled to the desert country of Midian.

For 40 years, he tended the flocks in the wilderness before God called him to deliver the Israelites from their bondage in Egypt. From a burning bush, God spoke to Moses, “I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about their suffering. So I have come down to rescue them from the hand of the Egyptians and to bring them up out of that land and spacious land, a land flowing with milk and honey” (Exodus 3:7–8).

God had chosen Moses as His personal envoy to Pharaoh to deliver His message: “Let my people go.” Despite being hand-picked, Moses argued with God, objecting four times with the following questions: Who am I? Who are You? What if they don’t believe me? To which God responds by telling Moses that He will go with him and that He is “I AM WHO I AM,” the ever-present, ever-existing One. He is the God who made the covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Exodus 3:15), and the One who is constantly present with Moses and with His people, Israel.

Finally, God gives Moses three signs of His power: 1) a staff that becomes a snake; 2) the hand that becomes leprous; and 3) water that turns to blood. When Moses again pleads with God to send someone else, God finally becomes angry and agrees to send Aaron, Moses’ brother, as his mouthpiece.

The Ten Plagues

There is a distinct pattern to the ten plagues that God brings upon the Egyptians. First, God employs the forces of nature to demonstrate His power over His creation. Second, the plagues are designed to mock the gods of Egypt, showing that God is in control over aspects they Egyptians believe only their gods controlled. Third, the plagues increase in intensity as Pharaoh’s heart continues to harden.

The first three plagues caused discomfort—the Nile River turned to blood; frogs overtook the land; the dust of Egypt became swarming gnats. The second three were more than just irritating. They were personally painful and destructive—swarms of flies covered the land; all the Egyptian livestock died of disease; horrible boils broke out on everyone in Egypt. The plagues hit closer and closer to home. From the fourth plague on, God distinguished between the Israelites and the Egyptians.

The Egyptians suffered, but the Israelites were spared. The third series of plagues not only produced selective destruction, but a growing sense of dread on the part of the Egyptians—hailstorms that killed all the slaves and animals left unprotected; locusts that covered Egypt and destroyed everything left after the hail; total darkness that covered Egypt (not Goshen where the Hebrews lived) for three days so that no one could move. God, however, hardened Pharaoh’s heart and Pharoah would not let God’s people leave.

Before the final — and most deadly plague — “The LORD said to Moses, ‘Pharaoh will refuse to listen to you—so that my wonders may be multiplied in Egypt.’ Moses and Aaron performed all these wonders before Pharaoh, but the LORD hardened Pharaoh’s heart, and he would not let the Israelites go out of his country” (Exodus 11:9—10).

The Final Plague

The last plague struck at the very heart of Pharaoh and his family—the firstborn males of every family in Egypt would die. This plague, which finally compelled Pharaoh to let Israel leave Egypt, was announced in two parts. The first announcement was to Pharaoh from Moses, who warned the Egyptian king of what was about to come upon all of Egypt (Exodus 11:4—10). The second was for the Israelites, and included God’s instructions for them regarding the Passover, which outlined the means through which God would protect them from the devastation of this deadly plague (Exodus 12:1–30).

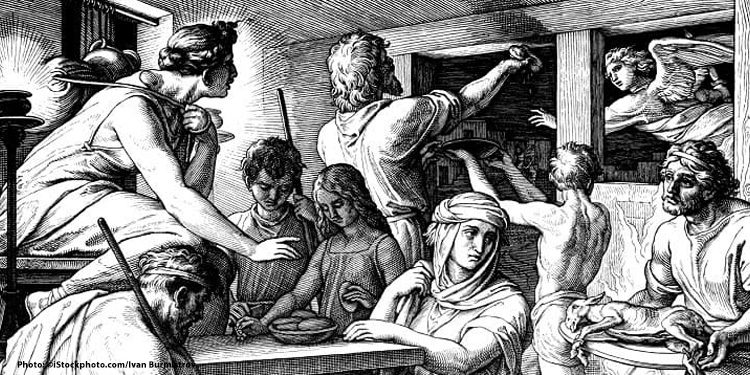

These instructions—sacrificing a young lamb, without blemish, smearing its blood on the lintels and doorposts of each Israelite household, baking bread without yeast so as to leave quickly, and eating this final meal while wearing traveling clothes—is the basis for the Passover, or the Feast of Unleavened Bread. When the final plague struck, and the “angel of death” came over Egypt, it would see the blood on the door frames and “pass over” those homes.

As God promised the people of Israel, “When I see the blood, I will pass over you. The plague of death will not touch you when I strike the land of Egypt” (Exodus 12:13). The lamb’s blood would be the only path to salvation—without it, their firstborn would die, along with those of the Egyptians. The Jewish captives were also told to eat the sacrificial lamb in haste as they prepared to leave Egypt in that first Exodus.

Passover and Exodus mark God’s redemption of Israel and their birth as a nation as Jewish families were liberated and led to the Promised Land.

How is Passover Celebrated?

Passover, one of the most significant festivals on the Jewish calendar, is celebrated with a blend of rich traditions, deep symbolism, and communal gatherings, marking the liberation of the Israelites from Egyptian slavery. This holiday, extending over eight days in the diaspora and seven days in Israel, is observed through a series of unique rituals and customs that resonate with the themes of freedom and remembrance.

The Preparation

The observance of Passover begins even before the holiday officially starts, with the meticulous removal of chametz (leavened bread and other fermented products) from Jewish homes. This act symbolizes the purging of pride and ego, reminiscent of the Israelites’ hasty departure from Egypt, when they did not have time to let their bread rise.

Many families engage in thorough spring cleaning, ensuring every crumb of chametz is discarded, sold, or stored away. This preparation culminates in the ritual search for chametz on the evening before Passover.

The Seder: A Night of Storytelling and Symbolism

At the heart of Passover is the seder, a ritual-packed feast held on the first two nights of the holiday. The seder is an elaborate affair where families and friends gather around the table to retell the story of the Exodus.

Central to this experience is the Haggadah, a text that guides the evening with prayers, songs, and narratives. Each component of the seder plate holds symbolic significance, from the bitter herbs (maror) representing the bitterness of slavery, to the charoset (a sweet paste) symbolizing the mortar used by the Israelite slaves.

What Is the Seder Plate?

The most visible part of the seder dinner is the plate of food eaten by those in attendance. The foods

eaten at the seder all symbolize different parts of the Israelites’ escape from Egypt.

One of the first steps Jews take to begin the seder, after the opening blessing and ritual hand-washing,

is to dip vegetables into saltwater. Any vegetable can be used for this symbol known as karpas, but it is customary to choose something green such as parsley, celery, or cucumber. The saltwater recalls the Israelites’ sweat and tears shed in slavery under Egyptian oppression. But the karpas also symbolizes spring, which is when God redeemed the children of Israel and when Passover is celebrated.

The Seder Meal in the Christian Bible

Some of the Jewish Passover rituals have carried over to the Christian holy days of Good Friday and Easter. Many of the aspects of communion or the Lord’s Supper are also taken from the Passover tradition. And just as we’ve learned how the seder meal holds symbolic significance in Judaism, the Last Supper does the same for Christians. With the items on the plate holding deep meaning and promising deliverance and salvation, just as God did for the Israelites, there is a direct connection between the two.

Jesus regularly observed the ceremonies of Passover by going to Jerusalem to celebrate this festival with his disciples. It was during the Passover celebration that Jesus taught his followers the significance of his approaching death and the season known to Christians worldwide as Easter (Luke 22:1-20).

Jesus underscored the importance of Passover to him as a Jew when he told his disciples, “I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer” (v. 15).

Recommended: Test Your Knowledge on Passover

And beyond the connection between the seder of the Jewish people and the communion of Christians, beyond our two faiths’ shared promise of deliverance, the seder can also remind Christians of the Exodus still going on, that of biblical prophecy being fulfilled. God promised in Isaiah that He would “assemble the outcasts of Israel, and gather together the dispersed of Judah from the four corners of the earth” (11:12 KJV).

Matzah—The Unleavened Bread of Affliction

One element on the seder table, however, stands out among the rest as a deeply symbolic and integral component of the Passover observance. That item is matzah (also spelled “matzo” or “matza”)—the flat, cracker-like bread that Scripture refers to as “unleavened bread” (Deuteronomy 16:3).

Jews are commanded to eat matzah for the entire duration of Passover, seven days in Israel and eight days outside the Holy Land. It is the only form of bread they may eat throughout the week-long holiday. The Bible says, “For seven days no yeast is to be found in your houses” (Exodus 12:19). Thus, the days just prior to Passover are a flurry of activity as Jews around the world clean their houses, searching for leavened products in every nook and cranny.

Although comprised of the simplest of ingredients, matzah is a multidimensional element with layers of meaning. It most powerfully captures the symbolism of the Passover story by representing both slavery and redemption in the Exodus narrative.

What Is the Spiritual Message of Matzah?

Matzah is known by several different names, and each speaks to a different aspect of its meaning. The Bible refers to matzah as “the bread of affliction” (Deuteronomy 16:3). It is also dubbed “the poor man’s bread,” as it is made up of only two ingredients—water and flour. It contains only the bare basics, signifying a life of poverty and difficulty. Through it, Jews can taste the harsh slavery of Egypt.

Recommended: A Taste of Passover

However, matzah is also referred to as “the bread of freedom.” It was the byproduct of God’s swift and miraculous salvation when the children of Israel were brought out of Egypt in such a hurry that they didn’t have time to allow their dough to rise. Matzah, therefore, is a symbol of Jewish freedom as well.

It became known as such a powerful symbol of Jewish identity that there have been times in history when making and consuming it has put Jews at risk. In the former Soviet Union, for example, the Communist regime waged war against organized religion and at times banned the making of matzah outright. Even during the times it was technically legal, it was never really safe, and thus was usually done in secret.

The Bread of Humility

Finally, in Judaism, matzah represents humility. It is low and flat like a humble person. In addition, it is simple, consisting of just flour and water; not at all fancy like many tasty and decorated leavened products. Chametz, leavened bread, on the other hand, represents arrogance. Bread is all puffed up and full of itself.

Eating unleavened bread, the bread of humility, for an entire week reminds Jews of their true place in the world. For all of humanity’s achievements and talents, we must remain humble, recognizing that everything is a gift from God. Whether you are Jewish or Christian, this is a lesson worth remembering—again and again.

What Is the Significance of the Lamb: Zeroah?

Zeroah is a piece of roasted lamb meat that reminds Jews of the lamb God told the Israelites to prepare the night before they were freed from slavery. It also reminds Jews that during the plague of the firstborn, God passed over the houses of the Israelites who had placed the blood of a slaughtered lamb on their doorposts. Finally, the roasted bone encourages Jews to remember that just as God saved the Israelites thousands of years ago, He can do the same for us today.

The Seder Plate: Food for Thought | International Fellowship of Christians and Jews (ifcj.org)

What Is the Significance of the Egg: Beitza?

The beitza, or egg, which is boiled and then roasted, represents a second offering that was brought during Temple times. In Judaism, an egg symbolizes mourning and is the traditional food of mourners. On Passover night, Jews remember that they still mourn the loss of the Holy Temple and that they yearn for the time when the Third Temple will be built. And while an egg recalls mourning, it also is a symbol of birth, another theme of Passover. It is through the slavery in Egypt and the subsequent redemption that the nation of Israel was born.

What Are the Bitter Herbs—Maror and Hazeret?

Maror (bitter herbs) and hazeret (bitter vegetables), which can be substituted with horseradish and romaine lettuce, remind Jews of the Israelites’ bitter lives as Pharaoh’s slaves. On this night when Jews celebrate their physical and spiritual freedom, they remember that the things people usually become enslaved to—temptations, addictions, or other vices—often start off innocuously before becoming enslaving and self-defeating. They remember how bitter slavery is—whether physical, emotional, or spiritual—and thank God for helping them achieve full freedom.

What Is Haroset?

Haroset — a mixture of apples, nuts, and grape juice — reminds Jews of the mixture that the Israelite slaves used to make bricks for Pharaoh, and of the hard work the slaves were forced to do. However, even though the haroset recalls the bitterness of slavery, it tastes sweet, showing that even in bitter times, we can always find something sweet in our lives, and that bitter times are eventually followed by the sweetness of redemption.

Learning Passover Greetings

During Passover, it’s customary to exchange holiday greetings with family and friends. So what’s the best way to wish someone a “Happy Passover?” There are several ways to share holiday greetings with those celebrating Passover.

- Chag Sameach (Chahg Sa-MAY-Ach) is the general Hebrew expression that means “happy holiday” and can be used for any Jewish observance.

- Chag Pesach Sameach (Chahg pay-SAKH Sa-MAY-Ach) is Hebrew for “Happy Passover.”

- Gut Yuntiff (Guht YON-tiff) is the Yiddish version of the greeting “Good Yom Tov,” which means “good day” and can be used on Passover or any major Jewish holidays.

- “Kosher and Joyous Passover” is the standard greeting in English-speaking countries as many Jewish families are cleaning their homes to be chametz-free and kosher for Passover.

Discover the inspirational insights on Passover with our Passover Devotional Guide.

Test your skills on Passover with our crossword and word search activities.