Mark Twain and the Lost Opportunity

Stand for Israel | December 18, 2019

Through many programs, and thanks to our faithful donors, The Fellowship is able to do much to alleviate the suffering of needy Jews across the former Soviet Union (FSU). But long before Eastern Europe was the FSU or even actively being ruled by the Soviet Union, the region’s Jews were often persecuted or worse. And because their existence was plagued by anti-Semitic pogroms and lives of poverty, the kindhearted folks in America did what they could to help, holding events and raising money.

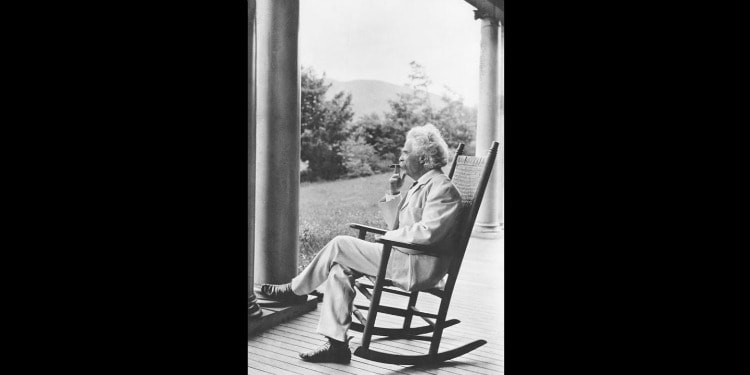

One such event, held on this date in 1905 (the same year the leisurely picture seen above was made), was headlined by Sarah Bernhardt, the most famous actress of the day, and beloved author Mark Twain. Since our words surely can’t touch those of Mr. Clemens, we’ll just provide the speech he gave that day in New York City, one with a “moral” and a “lesson” and a “lament” and a discussion of opportunities lost:

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN,—It seems a sort of cruelty to inflict upon an audience like this our rude English tongue, after we have heard that divine speech flowing in that lucid Gallic tongue.

It has always been a marvel to me—that French language; it has always been a puzzle to me. How beautiful that language is. How expressive it seems to be. How full of grace it is.

And when it comes from lips like those, how eloquent and how liquid it is. And, oh, I am always deceived—I always think I am going to understand it.

Oh, it is such a delight to me, such a delight to me, to meet Madame Bernhardt, and laugh hand to hand and heart to heart with her.

I have seen her play, as we all have, and oh, that is divine; but I have always wanted to know Madame Bernhardt herself—her fiery self. I have wanted to know that beautiful character.

Why, she is the youngest person I ever saw, except myself—for I always feel young when I come in the presence of young people.

I have a pleasant recollection of an incident so many years ago—when Madame Bernhardt came to Hartford, where I lived, and she was going to play and the tickets were three dollars, and there were two lovely women—a widow and her daughter—neighbors of ours, highly cultivated ladies they were; their tastes were fine and elevated, but they were very poor, and they said “Well, we must not spend six dollars on a pleasure of the mind, a pleasure of the intellect; we must spend it, if it must go at all, to furnish to somebody bread to eat.”

And so they sorrowed over the fact that they had to give up that great pleasure of seeing Madame Bernhardt, but there were two neighbors equally highly cultivated and who could not afford bread, and those good-hearted Joneses sent that six dollars—deprived themselves of it—and sent it to those poor Smiths to buy bread with. And those Smiths took it and bought tickets with it to see Madame Bernhardt.

Oh yes, some people have tastes and intelligence also.

Now, I was going to make a speech—I supposed I was, but I am not. It is late, late; and so I am going to tell a story; and there is this advantage about a story, anyway, that whatever moral or valuable thing you put into a speech, why, it gets diffused among those involuted sentences and possibly your audience goes away without finding out what that valuable thing was that you were trying to confer upon it; but, dear me, you put the same jewel into a story and it becomes the keystone of that story, and you are bound to get it—it flashes, it flames, it is the jewel in the toad’s head—you don’t overlook that.

Now, if I am going to talk on such a subject as, for instance, the lost opportunity—oh, the lost opportunity. Anybody in this house who has reached the turn of life—sixty, or seventy, or even fifty, or along there—when he goes back along his history, there he finds it mile-stoned all the way with the lost opportunity, and you know how pathetic that is.

You younger ones cannot know the full pathos that lies in those words—the lost opportunity; but anybody who is old, who has really lived and felt this life, he knows the pathos of the lost opportunity.

Now, I will tell you a story whose moral is that, whose lesson is that, whose lament is that.

I was in a village which is a suburb of New Bedford several years ago—well, New Bedford is a suburb of Fair Haven, or perhaps it is the other way; in any case, it took both of those towns to make a great centre of the great whaling industry of the first half of the nineteenth century, and I was up there at Fair Haven some years ago with a friend of mine.

There was a dedication of a great town-hall, a public building, and we were there in the afternoon. This great building was filled, like this great theatre, with rejoicing villagers, and my friend and I started down the centre aisle. He saw a man standing in that aisle, and he said “Now, look at that bronzed veteran—at that mahogany-faced man. Now, tell me, do you see anything about that man’s face that is emotional? Do you see anything about it that suggests that inside that man anywhere there are fires that can be started? Would you ever imagine that that is a human volcano?”

“Why, no,” I said, “I would not. He looks like a wooden Indian in front of a cigar store.”

“Very well,” said my friend, “I will show you that there is emotion even in that unpromising place. I will just go to that man and I will just mention in the most casual way an incident in his life. That man is getting along toward ninety years old. He is past eighty. I will mention an incident of fifty or sixty years ago. Now, just watch the effect, and it will be so casual that if you don’t watch you won’t know when I do say that thing—but you just watch the effect.”

He went on down there and accosted this antiquity, and made a remark or two. I could not catch up. They were so casual I could not recognize which one it was that touched that bottom, for in an instant that old man was literally in eruption and was filling the whole place with profanity of the most exquisite kind. You never heard such accomplished profanity. I never heard it also delivered with such eloquence.

I never enjoyed profanity as I enjoyed it then—more than if I had been uttering it myself. There is nothing like listening to an artist—all his passions passing away in lava, smoke, thunder, lightning, and earthquake.

Then this friend said to me: “Now, I will tell you about that. About sixty years ago that man was a young fellow of twenty-three, and had just come home from a three years’ whaling voyage. He came into that village of his, happy and proud because now, instead of being chief mate, he was going to be master of a whaleship, and he was proud and happy about it.

“Then he found that there had been a kind of a cold frost come upon that town and the whole region roundabout; for while he had been away the Father Mathew temperance excitement had come upon the whole region. Therefore, everybody had taken the pledge; there wasn’t anybody for miles and miles around that had not taken the pledge.

“So you can see what a solitude it was to this young man, who was fond of his grog. And he was just an outcast, because when they found he would not join Father Mathew’s Society they ostracized him, and he went about that town three weeks, day and night, in utter loneliness—the only human being in the whole place who ever took grog, and he had to take it privately.

“If you don’t know what it is to be ostracized, to be shunned by your fellow-man, may you never know it. Then he recognized that there was something more valuable in this life than grog, and that is the fellowship of your fellow-man. And at last he gave it up, and at nine o’clock one night he went down to the Father Mathew Temperance Society, and with a broken heart he said: ‘Put my name down for membership in this society.’

“And then he went away crying, and at earliest dawn the next morning they came for him and routed him out, and they said that new ship of his was ready to sail on a three years’ voyage. In a minute he was on board that ship and gone.

“And he said—well, he was not out of sight of that town till he began to repent, but he had made up his mind that he would not take a drink, and so that whole voyage of three years was a three years’ agony to that man because he saw all the time the mistake he had made.

“He felt it all through; he had constant reminders of it, because the crew would pass him with their grog, come out on the deck and take it, and there was the torturous Smell of it.

“He went through the whole, three years of suffering, and at last coming into port it was snowy, it was cold, he was stamping through the snow two feet deep on the deck and longing to get home, and there was his crew torturing him to the last minute with hot grog, but at last he had his reward. He really did get to shore at last, and jumped and ran and bought a jug and rushed to the society’s office, and said to the secretary:

“‘Take my name off your membership books, and do it right away! I have got a three years’ thirst on.’

“And the secretary said: ‘It is not necessary. You were blackballed!’”