A Holocaust Survivor’s Daughter on How She Honors Her Family

The Fellowship | February 3, 2020

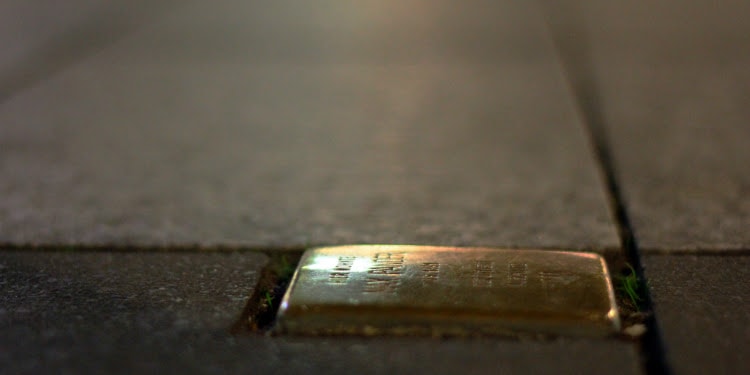

Walking on the streets of Europe, you may be surprised to see “stumbling stones,” or tiny brass-plated cobblestones placed into sidewalks. They are part of a project started by a German artist to commemorate where Nazi victims once lived.

Writing at TIME magazine, Helen Epstein shares why she chose to have her own loved ones, who perished in the Holocaust, to be honored in this inspiring way:

No one in my immediate family has a tombstone, though several generations of my ancestors do in what is now the Czech Republic. During the Second World War, my father’s family was gassed to death in Auschwitz and my mother’s parents were shot into an open pit at a small extermination site in what is now Belarus. My parents survived the Nazi concentration camps and died of natural causes. Perhaps in solidarity with their families, they chose to be cremated and asked their children to scatter their ashes in nature. We did so…

The names of my family members, along with 77, 290 others, are painted on the walls of one of the oldest synagogues in Prague. I’ve written about their lives in several books yet I wished for a more concrete memorial that would ground their names in the place where they lived full lives. Then I read about the artist Gunter Demnig’s stolpersteine, German for “stumbling stones.”

…You can’t plan a museum visit or stand in line for a ticket to encounter the largest decentralized memorial in the world; you stumble upon the stones. They are meant to surprise, provoke, and trigger reflection. When someone stumbles in Germany, a folk saying has it that “a Jew must be buried here,” raising the idea of an invisible history. A statue or plaque usually invites you to look up; stolpersteine force you to bend over in order to read. They also marked the place a person lived a life – not where it was cut off.